THE LAW'S EFFECTS ON SAMPLING

|

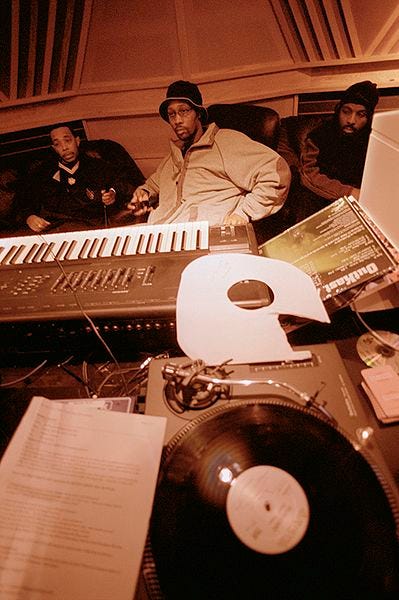

| Dr. Dre in the studio during the recording sessions for 2001 (late 1990's) |

Ever since

sampling became a part of pop culture, the legality of using copyrighted music

as samples has always been a concern in the music industry. One of the first

rap songs to be threatened with a lawsuit was the iconic “Rapper’s Delight” in

1979. After hearing the song played at a night club, Chic members Nile Rogers

and Bernard Edwards noticed the obvious similarities to their hit single “Good

Times” and later threatened to sue Sugar Hill Records for copyright

infringement, which later resulted in the members of Chic receiving song

writing credits.

Since the

“Rapper’s Delight” case, not many other major lawsuits occurred until the turn of the ‘90s when sampling began to reach its cultural and creative peak. One

of the first major copyright infringement suits to be brought up against a

rapper for sampling was in 1990 when representatives of Queen and David Bowie threatened

to sue pop rapper Vanilla Ice. This was due to his hit single “Ice Ice Baby”

(that everybody knows) containing a blatant sample of Queen and David Bowie’s

famous collaborative single “Under Pressure” to form the beat of the song. Unlike

most rap songs of the time, Vanilla Ice’s track sampled a very well-known and

iconic pop song to create another well-known and iconic pop song and it didn’t take long for listeners

to recognize the beat from “Under Pressure.”

The case was later settled out of court and Queen and David Bowie were given song writing credits and an undisclosed sum. Even though “Ice Ice Baby” became an international hit, becoming the first hip hop single to top the Billboard Hot 100, Vanilla Ice received a lot of criticism from the public and the media for “ripping off” Bowie and Queen’s hit song, which most likely heightened after Queen’s frontman Freddie Mercury died late 1991.

The case was later settled out of court and Queen and David Bowie were given song writing credits and an undisclosed sum. Even though “Ice Ice Baby” became an international hit, becoming the first hip hop single to top the Billboard Hot 100, Vanilla Ice received a lot of criticism from the public and the media for “ripping off” Bowie and Queen’s hit song, which most likely heightened after Queen’s frontman Freddie Mercury died late 1991.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1539246-1226990219.jpeg.jpg) |

| A later 12” vinyl pressing of “Ice Ice Baby” with Bowie and Queen listed as writers (2008) |

The Vanilla Ice lawsuit brought up a lot of discussion about

the links between plagiarism and sampling. Many other popular artists soon

followed suit and began to sue rappers for unauthorized sampling.

Around the same time of the Vanilla

Ice controversy, Tone-Lōc

was sued by Van Halen for the unauthorized sampling of their 1978 song “Jamie’s

Crying” into the song “Wild Thing.” Ton Lōc originally didn’t think his debut single would become such a

big hit, so he ignored initial requests from Van Halen’s management to pay a flat

fee and he even stated that he didn’t even know the sample his producer used was from Van Halen song until the track became popular. An out-of-court

settlement was eventually reached, and the original members of Van Halen were awarded $180,000.

Another

notable copyright infringement case occurred in 1990 when MC Hammer was sued by

Rick James for the unauthorized sampling of James’ 1981 hit song “Super Freak”

into (the now arguably even more iconic) “U Can’t Touch This.” Unlike the other

cases, MC Hammer did get authorization from Rick James’ lawyers to use the

sample, but this was done behind the artist’s back. Even though James received a rise in popularity, airplay and record sales, along with thousands of dollars

in royalties from MC Hammer, he still didn’t like his songs being sampled. He

then filed a lawsuit in order to gain song writing credits for the track and

won the case, which ironically resulted in him winning two Grammy Awards as a co-writer for “U Can’t

Touch This” later that year.

Tone-Lōc - Wild Thing (1989)

MC Hammer - U Can't Touch This (1990)

|

| Courtroom sketch of Led Zeppelin frontman Robert Plant and gutiarist Jimmy Page during the "Stairwaty to Heaven" copyright trial (2017) |

Even though

sampling-related lawsuits started to pop up much more often during the late ‘80s

and early ‘90s, many hip hop producers and rappers still felt safe using samples on their records if the sources weren’t too obvious and that they were

mixed with other samples and edited enough into becoming almost unrecognizable to the

average listener. Artists like Public Enemy and the Beastie Boys were able to

avoid lawsuits by using more unique, unrecognizable samples (not from recent

hit songs) and editing them (speeding up, slowing down, reversing, adding

effects, etc.) or cutting them down to small portions to avoid detection.

The first major

threat towards the art of sampling came in the form of a lawsuit in 1991. About

two years after the release of De La Soul’s highly acclaimed debut album 3 Feet High and Rising, the rap trio, their producer Prince Paul and their label Tommy Boy were sued by members of the veteran rock band The Turtles for a staggering $2.5 million.

This was due to a 12-second segment of the Turtles’ 1969 song “You Showed Me”

being used on the track “Transmitting Life from Mars.” Unlike the Vanilla Ice and MC Hammer cases, the track wasn’t even

technically a song, rather a skit that would interlude into the next track “Eye

Know.”

De La Soul and the Turtles settled outside of court with the two bandmates claiming to have been awarded $1.7 million, although De La Soul denied that they paid that much. Out of the sixty (give or take) artists they sampled from, they probably felt somewhat relieved that only one of them filed a lawsuit against them, and probably somewhat worried about the other artists that could possibly sue them, which included big names like Billy Joel, The Beatles, Michael Jackson, and Johnny Cash.

In the video below, Vin Rican of Wax Only showcases many of the samples contained on 3 Feet High and Rising, including the infamous Turtles sample.

De La Soul and the Turtles settled outside of court with the two bandmates claiming to have been awarded $1.7 million, although De La Soul denied that they paid that much. Out of the sixty (give or take) artists they sampled from, they probably felt somewhat relieved that only one of them filed a lawsuit against them, and probably somewhat worried about the other artists that could possibly sue them, which included big names like Billy Joel, The Beatles, Michael Jackson, and Johnny Cash.

In the video below, Vin Rican of Wax Only showcases many of the samples contained on 3 Feet High and Rising, including the infamous Turtles sample.

Discover Samples On De La Soul's '3 Feet High And Rising' #WaxOnly (Power 106 Los Angeles - 2018)

Later on

that year, Biz Markie was sued in a similar fashion by pop singer-songwriter

Gilbert O’Sullivan after a portion of his 1972 single “Alone Again (Naturally)”

was sampled on the track “Alone Again” from Biz Markie’s 1991 album I Need a Haircut album. Biz Markie did attempt

to get clearance for the sample and was declined, but he released the album

with the sample intact anyway. What made this case stand out among others at

the time was that, instead of being settled out of court, the judge ruled in

favor of the plaintiff, ordering the rapper to pay $250,000 in damages,

restricting any further sales of the album, and even referring him to

criminal court on the grounds of theft, although the rapper was never charged. He

released his next album titled All

Samples Cleared! in 1993.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2439370-1541778800-7115.jpeg.jpg) |

| J-card of the cassette release of I Need a Haircut (1991) |

Because of these

two cases, sampling began to slowly decline and sample-heavy albums like 3 Feet High and Rising and the Beastie

Boys’ Paul’s Boutique became much harder

to make as the years went on. It would cost far too much money to clear all the

samples on records like De La Soul’s, so many rap artists began to resort back

to having original beats created for them, using sampling as little as

possible.

De La Soul's lack of sample clearances is is likely part of the reason why 3 Feet High and Rising hasn’t had an official reissue since 2001 (despite some limited vinyl releases in 2013 and 2019) and the album’s noticeable omission from all streaming services, including Spotify, Apple Music, and Tidal, since the record label likely feared more lawsuits to appear over uncleared samples. Because of this, physical copies of the album are now considered highly collectible and sought after by collectors and audiophiles with original 3 Feet High and Rising LPs, CDs and cassettes being sold on sites like eBay for a lot of money, much more than most other original copies of classic hip hop albums.

Biz Markie's I Need a Haircut is similarly not found on any streaming services and all physical copies that were made after the lawsuit had Alone Again omitted. The album is available in its entirety on YouTube. 3 Feet High and Rising used to be on YouTube, but was recently removed, which increased the demand for physical copies even more, as you can see below.

De La Soul's lack of sample clearances is is likely part of the reason why 3 Feet High and Rising hasn’t had an official reissue since 2001 (despite some limited vinyl releases in 2013 and 2019) and the album’s noticeable omission from all streaming services, including Spotify, Apple Music, and Tidal, since the record label likely feared more lawsuits to appear over uncleared samples. Because of this, physical copies of the album are now considered highly collectible and sought after by collectors and audiophiles with original 3 Feet High and Rising LPs, CDs and cassettes being sold on sites like eBay for a lot of money, much more than most other original copies of classic hip hop albums.

Biz Markie's I Need a Haircut is similarly not found on any streaming services and all physical copies that were made after the lawsuit had Alone Again omitted. The album is available in its entirety on YouTube. 3 Feet High and Rising used to be on YouTube, but was recently removed, which increased the demand for physical copies even more, as you can see below.

|

| Recently sold original copies of 3 Feet High and Rising on eBay (2019) |

|

| 3 Feet High and Rising listed on Amazon.ca (2019) |

Many hip hop

producers during the early ‘90s were not really used to going back to the old

ways of creating beats on synthesizers and drum machines, but one rapper and

producer in particular embraced the new sampling guidelines and created a new

sound entirely.

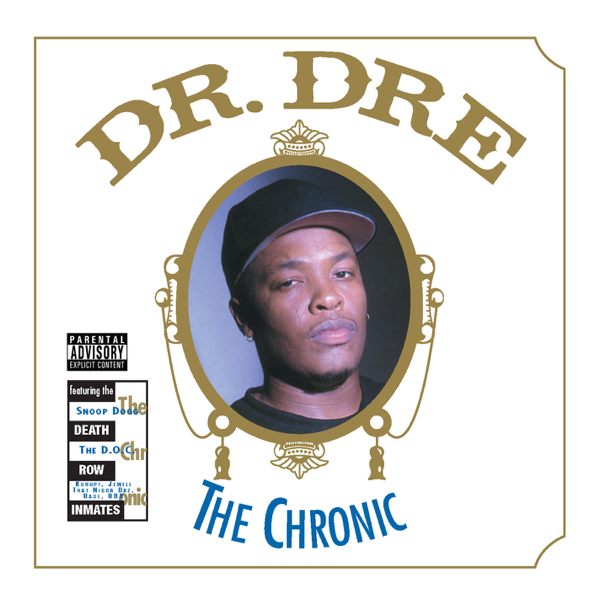

On December 15, 1992, after his release from Ruthless Records and his falling out with N.W.A., Dr. Dre released his game changing debut solo album The Chronic. The album’s production, also handled by Dre, was considered very innovative and unique at the time. By using sampling to a minimum, Dr. Dre created Parliament-Funkadelic inspired synthesized funk beats which, backed with smooth, laid-back rapping, were hypnotic, melodic, and much more “chill” than the aggressive, sample-heavy styles of gangsta rap.

Although sampling was still used on the album, it wasn’t overbearing and most of the album’s beats were synthesized with light sampling layered in the background; many samples were even recreated with synthesizers, a practice that soon became common to avoid sample clearance issues. While retaining the gangsta lyrical subject matter and persona, the album spawned the hit single “Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thang,” which many critics consider to be one of the greatest hip hop songs of all time. The album also launched the careers of Snoop Dogg, Kurupt, Nate Dogg, and Warren G, and created its own new subgenre of hip hop called g-funk, a genre which continued to influence many hip hop and R&B artists to this day.

On December 15, 1992, after his release from Ruthless Records and his falling out with N.W.A., Dr. Dre released his game changing debut solo album The Chronic. The album’s production, also handled by Dre, was considered very innovative and unique at the time. By using sampling to a minimum, Dr. Dre created Parliament-Funkadelic inspired synthesized funk beats which, backed with smooth, laid-back rapping, were hypnotic, melodic, and much more “chill” than the aggressive, sample-heavy styles of gangsta rap.

Although sampling was still used on the album, it wasn’t overbearing and most of the album’s beats were synthesized with light sampling layered in the background; many samples were even recreated with synthesizers, a practice that soon became common to avoid sample clearance issues. While retaining the gangsta lyrical subject matter and persona, the album spawned the hit single “Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thang,” which many critics consider to be one of the greatest hip hop songs of all time. The album also launched the careers of Snoop Dogg, Kurupt, Nate Dogg, and Warren G, and created its own new subgenre of hip hop called g-funk, a genre which continued to influence many hip hop and R&B artists to this day.

|

| The Chronic (1992) |

Even though

many of the mainstream rappers were using g-funk inspired production mixed with

minimal amounts of sampling to avoid copyright issues, many of the more underground

and lesser-known rappers still used sampling to a great extent. A lot of these

rappers also realized that sampling from more obscure tracks by lesser-known

artists would more than likely allow them to get away with sampling without clearance, the more

obscure, the better.

This became a major production technique for the Wu-Tang Clan’s de facto leader and main producer RZA. During the production of the Wu-Tang Clan’s acclaimed debut album Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), he used samples from old, lesser-known soul songs like Wendy Rene’s “After Laughter (Comes Tears)” for “Tearz” and the Charmels’ “As Long As I’ve Got You” for “C.R.E.A.M.,” a song that would later become a hit single and one of hip hop’s most iconic songs.

This became a major production technique for the Wu-Tang Clan’s de facto leader and main producer RZA. During the production of the Wu-Tang Clan’s acclaimed debut album Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), he used samples from old, lesser-known soul songs like Wendy Rene’s “After Laughter (Comes Tears)” for “Tearz” and the Charmels’ “As Long As I’ve Got You” for “C.R.E.A.M.,” a song that would later become a hit single and one of hip hop’s most iconic songs.

In contrast

to The Chronic, the Wu-Tang Clan’s

debut album featured very raw, gritty, and eerie beats over the aggressive

rapping of the nine original members of the group, along with record scratching by the

4th Disciple, another production technique that began to die down during the ‘90s. RZA also implemented dialogue and audio from scenes of

multiple Chinese/Hong Kong (English dubbed) martial arts films like Shaolin and Wu-Tang and Five Deadly Venoms to give the record a

very unique style and sound that would become a staple in the Wu-Tang Clan’s group and

solo discography.

|

| Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) (1993) |

After the

success and critical acclaim of the album, many of the Wu-Tang Clan members

recorded solo albums while remaining in the group in order to get the most out of

the market. Most of the Wu-Tang Clan rappers’ solo albums featured guest appearances

from other group's other members and affiliates and were mostly produced by RZA, who continued

his unique approach to production by sampling movie clips, world music, and

obscure soul music.

He did this in a way to make each album unique and fitting to the characteristics of the rapper in question; for example, Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… featured very eerie and dark, theatrical beats to match the aggressive rapping, dark lyricism and concept of the album, while Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s NI**A Please featured more funky and fast-pace party-style beats to match his outlandish and manic style of rapping and lyricism.

Even when RZA sampled from well-known artists like Sly and the Family Stone and Otis Redding, he was able to edit and cut up the sample enough to make it unrecognizable to the average listener, although RZA still had his fair share of lawsuits.

He did this in a way to make each album unique and fitting to the characteristics of the rapper in question; for example, Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… featured very eerie and dark, theatrical beats to match the aggressive rapping, dark lyricism and concept of the album, while Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s NI**A Please featured more funky and fast-pace party-style beats to match his outlandish and manic style of rapping and lyricism.

Even when RZA sampled from well-known artists like Sly and the Family Stone and Otis Redding, he was able to edit and cut up the sample enough to make it unrecognizable to the average listener, although RZA still had his fair share of lawsuits.

|

| RZA in the studio with records ready to be sampled |

Enter the Wu-Tang revitalized the East Coast rap scene

that was previously overshadowed by the g-funk rappers of the West Coast, and

sampling soon became relevant again, with landmark albums like Mobb Deep’s The Infamous, Nas’ Illmatic, and Black Moon’s Enta

da Stage using a similar production style to the likes of RZA. The Notorious B.I.G.'s debut album Ready to Die used a mix of East Coast and West Coast production techniques to give the album a wider appeal. Some of the tracks like "Gimme the Loot" featured raw, sample-based, RZA-inspired production, while others like "Big Poppa" featured a more g-funk inspired beat.

Even though

sampling had a short resurgence in popularity in the mid-90s, it began to slowly

die out again by the end of the decade, with mainly only underground rappers

getting the most out of sampling. As a reminder to the world that sampling is

in fact an art form and not theft or plagiarism, DJ Shadow released his debut

album Endtroducing… in 1996.

While not a rapper himself, DJ Shadow’s album contributed a lot to hip hop culture, being recognized by Guinness World Records as the first album to be created entirely from samples. Although the album took a while to find success, it became very popular among critics, other hip hop producers, rappers, and underground hip hop enthusiasts. It is now credited by many as one of the most influential instrumental albums ever made.

While not a rapper himself, DJ Shadow’s album contributed a lot to hip hop culture, being recognized by Guinness World Records as the first album to be created entirely from samples. Although the album took a while to find success, it became very popular among critics, other hip hop producers, rappers, and underground hip hop enthusiasts. It is now credited by many as one of the most influential instrumental albums ever made.

|

| Endtroducing... (1996) |

While this style

of production was later exemplified by critically acclaimed (but not

mainstream) producers and rappers like J Dilla, MF Doom and Common, sample-heavy hip

hop began to fade out of the mainstream almost completely by the end of the decade,

with many of the most acclaimed and popular up-and-coming rap artists like

OutKast, DMX and Eminem using mainly only synthesized beats to rap over.

Sampling was now almost exclusively used by the elite, like Dr. Dre and Jay-Z, who were able to afford to pay the high costs of sample clearances, and even then, they didn’t use sampling as much as most rappers did ten years prior. Rappers who wanted to get into the mainstream, sell a lot of records, have a lot of radio airplay, and sign to big name labels had to use sampling as little as possible since most record companies didn’t want to risk paying sample clearance fees for artists who might not even make it big and not make the money back.

Sampling was now almost exclusively used by the elite, like Dr. Dre and Jay-Z, who were able to afford to pay the high costs of sample clearances, and even then, they didn’t use sampling as much as most rappers did ten years prior. Rappers who wanted to get into the mainstream, sell a lot of records, have a lot of radio airplay, and sign to big name labels had to use sampling as little as possible since most record companies didn’t want to risk paying sample clearance fees for artists who might not even make it big and not make the money back.

By the mid

2000s, most popular rap songs featured no sampling whatsoever, with songs like

Snoop Dogg’s “Drop It Like It’s Hot” and 50 Cent’s “Candy Shop” relying solely

on synthesized beats. Hip hop was now more mainstream than ever, but many critics

and hip hop fans alike agreed that the mid 2000s was hip hop’s lowest point

based on creativity and quality.

Fortunately by the 2010s, sampling slowly began to become relevent again for a number of reasons that will be explored in the next post…

Below is a playlist of '90s hip hop tracks that continued to use sampling despite legal and financial risks. Notice how the music at the top of the playlist (early '90s) featured much more sampling than the music at the bottom (late '90s).

Below is a playlist of '90s hip hop tracks that continued to use sampling despite legal and financial risks. Notice how the music at the top of the playlist (early '90s) featured much more sampling than the music at the bottom (late '90s).

The History of Sampling: 1990 - 1999

Works Cited

"Alone Again." Discogs, accessed May 2019, www.discogs.com/composition/2fe93093-7bc3-4ec7-a531-fa24e7105181-Alone-Again.

“De La Soul – 3 Feet High and Rising.” Discogs, accessed May 2019, www.discogs.com/De-La-Soul-3-

“De La Soul – 3 Feet High and Rising.” Discogs, accessed May 2019, www.discogs.com/De-La-Soul-3-

“Enter the

Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) (1993).” WhoSampled,

accessed May 2019,

“First album

made completely from samples.” Guiness

World Records, 1996, accessed May 2019,

Cannon,

Sean. “Every Sample From De La Soul’s ‘3 Feet High And Rising,’ Ranked.” Discogs Blog, Discogs,

March 2019, blog.discogs.com/en/de-la-soul-3-feet-high-samples/.

Hart, Ron. “Tone

Love Talks His Debut Turning 30 & His Run-In With Eddie Van Halen.” Billboard, 25 Jan.

J., Miranda.

“15 TIMES RAPPERS WERE SUED OVER BEATS IN THE PAST YEAR.” XXL Mag, 7 Jan. 2015,

Jolly,

Natahn. “The Chance the Rapper lawsuit that could destroy the hip hop

industry.” The Industry Observer,

The

Brag Media, 14 Sep. 2017, theindustryobserver.thebrag.com/the-chance-the-rapper-lawsuit-that-could-

Jones, Russell

Tyrone “Ol’ Dirty Bastard.” “NI**A Please.” Spotify,

Elektra Records, 14 Sept. 1999,

Newton,

Matthew. “Is Sampling Dying?” Spin,

21 Nov. 2008, www.spin.com/2008/11/sampling-dying/.

POPBOXTV.

“The Story of Rapper’s Delight by Nile Rodgers.” YouTube, uploaded by POPBOXTV, 2 Mar.

Question

Time. “WU-TANG CLAN ORIGINS – How RZA’s 5-Year Plan Changed Hip Hop Forever.” YouTube,

15 June 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=_2jTeaOQjfE.

Rolling

Stone. “The Knack Sue Run-DMC Over “It’s Tricky” Riff.” Rolling Stone, 16 Sept. 2006,

Runtagh,

Jordan. “Songs on Trial: 12 Landmark Music Copyright Cases.” Rolling Stone, 8 June, 2016,

Songfacts. “Rapper’s

Delight by The Sugarhill Gang.” Songfacts,

accessed May 2019,

Songfacts. “U

Can’t Touch This by MC Hammer.” SongFacts,

accessed May 2019,

Turner,

David, Alysa Lechner, David Drake, Ernest Baker, Insanul Ahmed, and Brian

Josephs. “Every No. 1

Rap Song in Hot 100 History.” Complex, Complex Media, Inc., 15 Jul. 2015,

Wang,

Oliver. “20 Years Ago Biz Markie Got The Last Laugh.” The Record: Music News from NPR, NPR, 6

May, 2013, www.npr.org/sections/therecord/2013/05/01/180375856/20-years-ago-biz-markie-got-the-last-

Watson, Elijah

C. “30 Years Since ‘3 Feet High & Rising’ & De La Soul Still Isn’t In

Control Of Its Legacy.”

Okayplayer, March

2019, www.okayplayer.com/music/breakdown-de-la-soul-fight-tommy-boy-records-3-feet-

Woods, Corey

“Raekwon.” “Only Built 4 Cuban Linx…” Spotify,

Sony Music Entertainment, 1 Aug. 1995,

Young, Andre

“Dr. Dre.” The Chronic. Apple Music, Death Row Records, 15 Dec.

1992, 2001,

Image and Video Credits

1991 I Need a Haircut Cassette j-card. Discogs, uploaded by WolfXCIX, Biz Markie Cold Chillin' Records/Warner Bros. Records, 1991, 2018, www.discogs.com/Biz-Markie-I-Need-A-Haircut/release/2439370#.

3 Feet High and Rising Amazon.ca listing screenshot. Amazon, accessed May 2019, www.amazon.ca/3-Feet-High-Rising-Soul/dp/B000000HHE.

3 Feet High and Rising eBay.ca listings screenshot. eBay, accessed May 2019, www.ebay.ca/sch/i.html?_from=R40&_sacat=0&_sop=16&_nkw=3%20feet%20high%20and%20rising&LH_Complete=1&LH_Sold=1&rt=nc&_trksid=p2045573.m1684.

Edwards, Mona Shafer. "Robert Plant Jimmy Page Led Zeppelin Trial Illustration. Rolling Stone, article by Daniel Kreps, 18 Mar. 2017, www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/appeal-filed-in-led-zeppelin-stairway-to-heaven-copyright-trial-128902/.

Endtroducing... album cover. Rough Trade, DJ Shadow, Mo' Wax/RT UK, 16 Sep. 1996, 15 Dec. 08, www.roughtrade.com/us/music/endtroducing-747d9781-dddf-4adb-83c7-f56f5d464b72.

Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) album cover. Amazon UK, Wu-Tang Clan, Loud Records/RCA Records, 9 Nov. 1993, www.amazon.co.uk/Enter-Wu-Tang-36-Chambers-Clan/dp/B000024D0J.

Grey Organisation. 3 Feet High and Rising album cover. Album Art Exchange, De La Soul, uploaded by zbop, Tommy Boy Entertainment, 1989, albumartexchange.com/covers/97130-3-feet-high-and-rising-12?

3 Feet High and Rising Amazon.ca listing screenshot. Amazon, accessed May 2019, www.amazon.ca/3-Feet-High-Rising-Soul/dp/B000000HHE.

3 Feet High and Rising eBay.ca listings screenshot. eBay, accessed May 2019, www.ebay.ca/sch/i.html?_from=R40&_sacat=0&_sop=16&_nkw=3%20feet%20high%20and%20rising&LH_Complete=1&LH_Sold=1&rt=nc&_trksid=p2045573.m1684.

Edwards, Mona Shafer. "Robert Plant Jimmy Page Led Zeppelin Trial Illustration. Rolling Stone, article by Daniel Kreps, 18 Mar. 2017, www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/appeal-filed-in-led-zeppelin-stairway-to-heaven-copyright-trial-128902/.

Endtroducing... album cover. Rough Trade, DJ Shadow, Mo' Wax/RT UK, 16 Sep. 1996, 15 Dec. 08, www.roughtrade.com/us/music/endtroducing-747d9781-dddf-4adb-83c7-f56f5d464b72.

Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) album cover. Amazon UK, Wu-Tang Clan, Loud Records/RCA Records, 9 Nov. 1993, www.amazon.co.uk/Enter-Wu-Tang-36-Chambers-Clan/dp/B000024D0J.

Grey Organisation. 3 Feet High and Rising album cover. Album Art Exchange, De La Soul, uploaded by zbop, Tommy Boy Entertainment, 1989, albumartexchange.com/covers/97130-3-feet-high-and-rising-12?

Ice, Ice Baby (Flashback’s Funky Rewerk) 2008 12" promo label. Discogs, Vanilla Ice, uploaded by Disco_Freaks, Vicious Recordings, 2008, www.discogs.com/Vanilla-Ice-Ice-Ice-Baby-Flashbacks-Funky-Rewerk/release/1539246.

Power 106 Los Angeles. "Discover Samples On De La Soul's '3 Feet High And Rising' #WaxOnly." YouTube, presented by Vin Rican, 2 Mar. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVAKpKpU14k.

Photograph of Dr. Dre in the studio. Medium, article by Christopher Pierznik, 6 Aug. 2015,

Photograph of Dr. Dre in the studio. Medium, article by Christopher Pierznik, 6 Aug. 2015,

The Chronic album cover. Apple Music, Dr. Dre, Death Row Records, 1992, 2001, itunes.apple.com/us/album/the-chronic/6654037.

Väisänen, Mika. "RZA taking a break during a studio session." Medium, article by Gino Sorcinelli, 11 Dec. 2016,

No comments:

Post a Comment